As part of our #SmartHealthSystems study which examines the digital transformation of healthcare systems in 17 countries, we have visited five of these countries to take a closer look at what they have achieved. In each country, we have explored the political, cultural, technological and economic factors driving success as well the obstacles to advancing digitization strategies in healthcare. The findings of our cross-national study will be published in November 2018. Until then, we will be highlighting thought-provoking insights and best practices from other countries here in our blog. From Switzerland we’ve learned that despite the country’s federally fragmented health system, implementing a decentralized national electronic patient record system is feasible – as long as the hurdles are cleared along the way.

“Patients as fair game for hackers?” This was the headline of a 2015 article in the “Neue Züricher Zeitung” (NZZ) that quoted the Pirate Party on their concerns about dangerous security vulnerabilities affecting one particularly sensitive category of personal data: Information about the health of patients. The bone of contention was the introduction in Switzerland of the electronic patient record (Elektronisches Patientendossier, EPD). While the two cantons of Valais and Geneva were the first to pilot the EPDs, there was criticism from the Pirate Party of the substandard security of EPD systems against potential hacker attacks. Despite such objections, it is worth remarking that Switzerland could not be dissuaded from implementing the project, which since 2007 has been laid down as an activity area in the government’s national E-Health Strategy [PDF] towards the introduction of EPDs across the country.

About three years after Valais and Geneva launched their pilot EPD systems, Switzerland is indeed moving ever closer to a comprehensive service encompassing digital storage and the inter-institutional exchange of health-relevant patient data – as it is required to do so by law. All hospitals are required to change over to EPDs by mid-April 2020, and nursing homes by mid-April 2022.

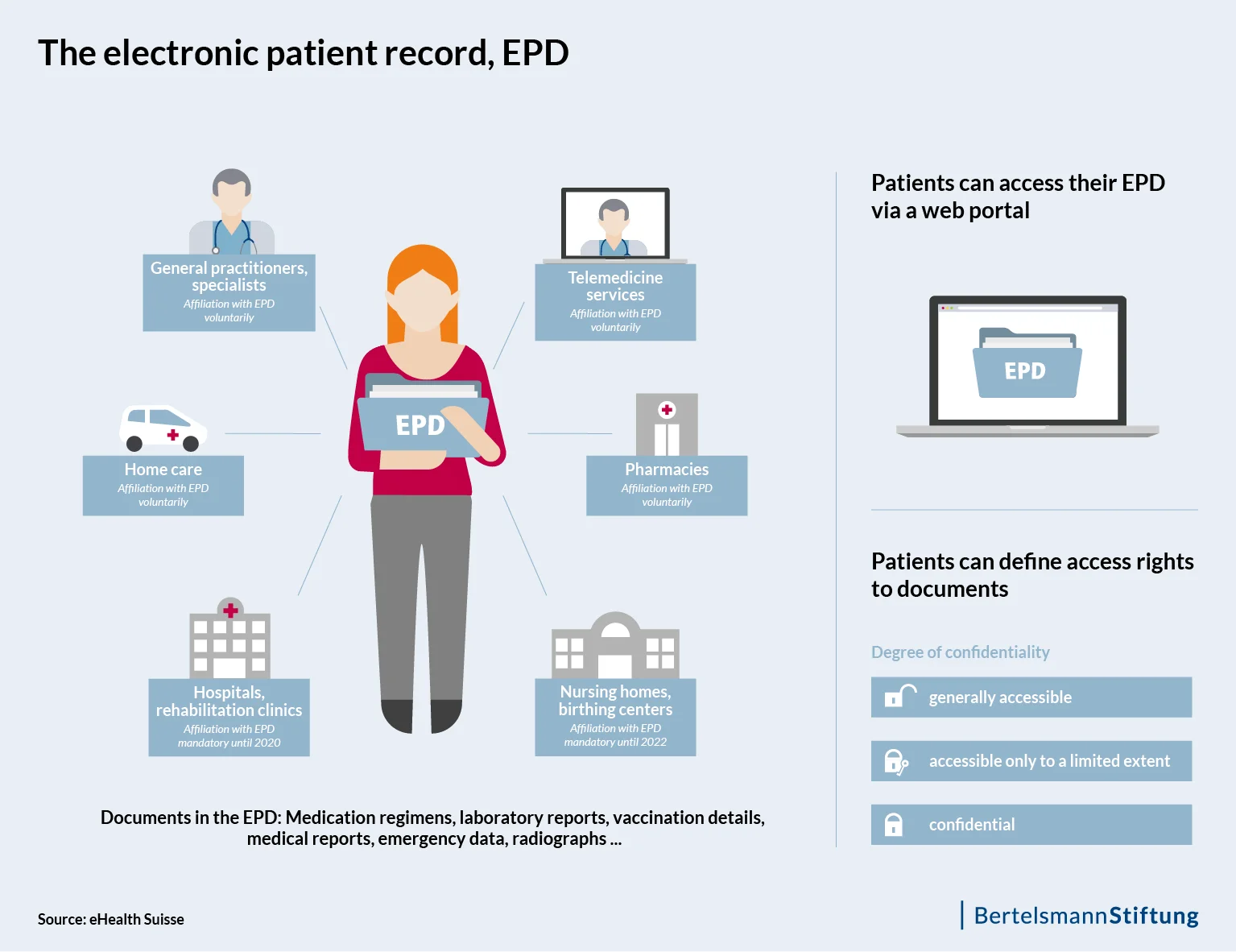

What this means is that healthcare professionals must be technically capable of inputting treatment-relevant documents such as x-rays into the electronic records. Moreover, every member of the public must have secure access to all of the treatment-relevant documents and information contained in their patient dossier. This implementing provision is established in Swiss Federal Law as a regulation on the electronic patient dossier (EPDG), which has been in force since April 2017. It is notable that an “e-health law” of this kind was introduced, despite the very limited federal competence in the health sector.

Principle of double voluntarism: no obligation for patients and physicians

For patients, the use of the EPD is voluntary. The patient decides whether they want to open – and consequently also own – an EPD or not. They also specify who else is able to view the documents. Freely practicing physicians or those working in an outpatient context are likewise not obligated to sign up for the EPD. The background to this is a threat by the umbrella organization for the Swiss medical profession, Berufsverband der Schweizer Ärzteschaft (FMH), to put the law to a referendum. A comment piece from the “Neue Züricher Zeitung” in early 2017 called the introduction of the EPD a “forceps delivery” and pointed out that the EPD can only be a success story and fulfill the promise of better medicine if is accepted by patients and physicians. At the same time, it was precisely this political gimmick of ‘double voluntarism’ that helped to move the various stakeholders in the Swiss healthcare system in the direction of a national patient record system.

Among other things, the Swiss National Council defines “better medicine” as an improvement in the quality of treatment, an increase in patient safety and an increase in cost efficiency. On the other hand, there remain a series of hurdles to overcome before any such effects can actually come to pass across the country. The Swiss Federal Office of Public Health (FOPH) had originally envisaged the first patients opening their EPDs from the middle of this year. However, following the first tests of the EPD systems in September 2017, the FOPH admitted that the expenditure on the side of the cantons would be higher than anticipated.

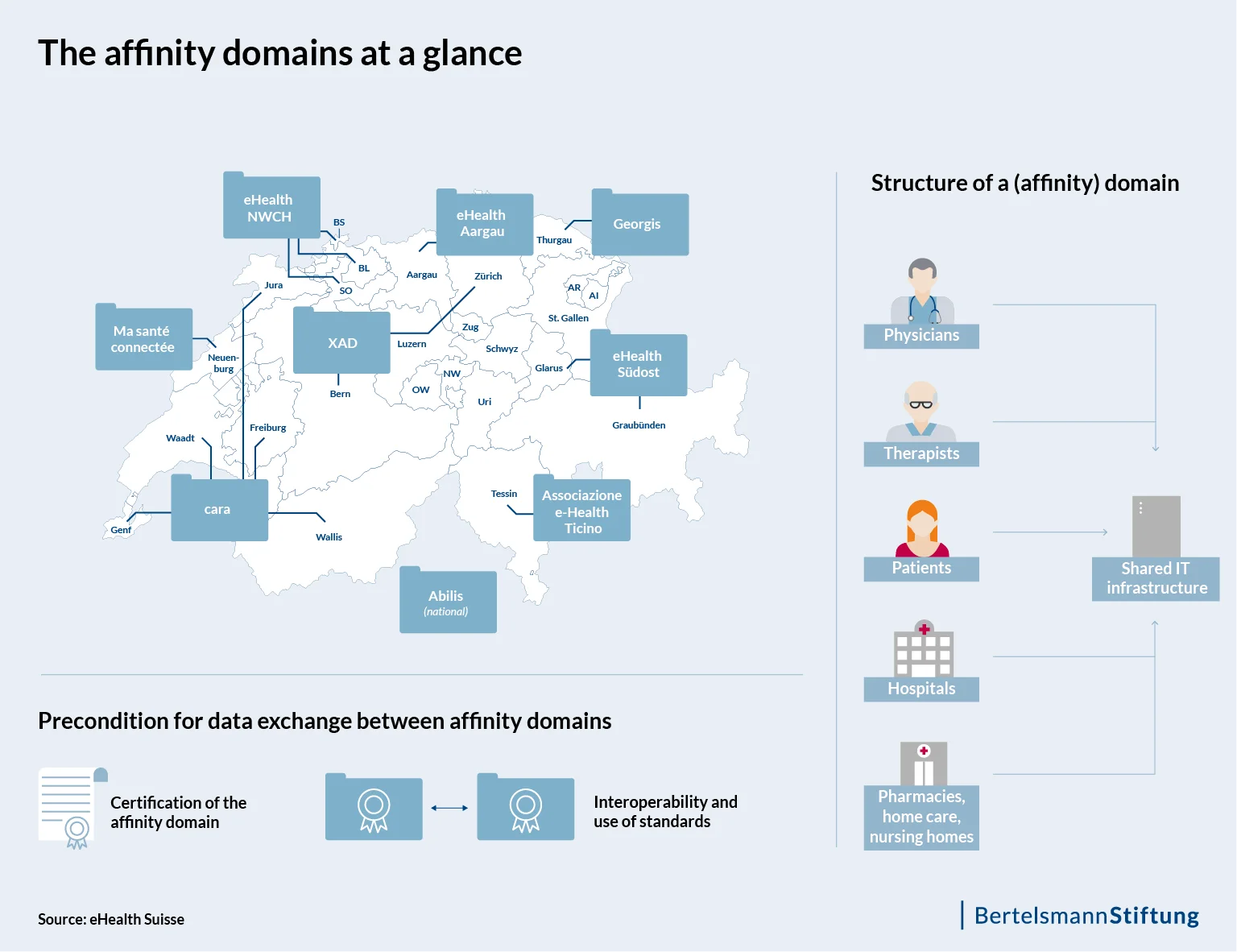

One reason for this is that – in keeping with its healthcare system – Switzerland is taking the federal approach. This means that implementation of the EPD is carried out at the cantonal level by means of individual autonomous projects, namely so-called EPD collectives and “affinity domains” (Stammgemeinschaften). A domain encompasses regional health professionals and their institutions, and enables the patient to open a personal EPD that they can access through a portal. Affinity domains also offer patients the opportunity to manage their EPDs, including the allocation of access rights or the addition of personal data such as a glasses prescription or living will.

These technical and organizational network structures can be established either in individual cantons or across several cantons. In French-speaking Switzerland, for example, five cantons have joined together to form a planned affinity domain going by the name of Cara. In In this way, an exchange of data between different domains across cantonal borders is only possible if the domain has the corresponding federal certification.

The coordinating body between the federal government and the cantons is eHealth Suisse, whose contracting authority is the FOPH. eHealth Suisse was involved in the development of the second draft of the national E-Health Strategy [PDF], and while it is not able to intervene in implementation processes in a regulatory sense, the coordinating body is integral for the domains, which are aiming at a uniform appearance at the end of the EPD implementation. While individual EPDs may differ in their configuration, it is hoped that the general public will eventually view the EPD as a single-source system and thus understand it more straightforwardly.

The federal certification also serves this purpose: certified domains are permitted to use an EPD logo as a seal of quality, signaling to the public that it is a trusted EPD portal. By mid-October 2017, the FOPH had received ten applications for financial assistance in the establishment of (affinity) domains (see figure). If successful, these are in line to receive certification in the second half of 2019. The federal government has made 30 million Swiss francs available as start-up financing [PDF] for the affinity domains.

Interoperability in a fragmented system of immense complexity

All told, the requirements that are placed on this fragmented system are immense, while the work steps for implementing the technical infrastructure are precisely defined. Modifications to regulations in the areas of security and data protection are also necessary, both to ensure security and to assist the progress of digitization. And although the EPD is based on international standards, the interplay of these work steps is “unique worldwide in its complexity,” according to a communication [PDF] from the FOPH and eHealth Suisse. Of course, it is not possible to verify this assertion. That the system is complicated is undisputed.

Another major hurdle that must be addressed before the EPD can be implemented is its interoperability. According to EPD experts, it will be possible to deliver genuine, measurable added value and to ultimately reduce healthcare costs only if it features interoperability and open interfaces.

Admittedly, a study from the consulting firm KPMG estimates the savings potential of the EPD to be at least 300 million francs per year – achieved exclusively through a smaller amount of wasted time. The research institute empirica also comes to a conclusion [PDF] that includes a net socioeconomic benefit of about 200 million francs annually. However, to achieve this outcome it will be absolutely essential that the preparation and processing of the data within the dossier is in the form of structured, clear, contextual, relevant and helpful information: “15 years of digitization know-how […] have taught me that electronic documents bring little more than a paper file,” said Roland Naef, Head of Medical Applications and Services at the University Hospital Zurich at the Swiss E-Health Forum in Bern in early March. For a physician with a time budget of five to fifteen minutes per patient, searching through a multi-page EPD and picking out the relevant data before questioning the patient is not the most sensible or helpful of approaches.

The problem here is that the development of well thought out IT infrastructures presents a huge challenge to the affinity domains, which is why they depend on start-up financing from the federal government – and on IT partners. At the end of the day, the crucial task is to develop viable business models and to answer the question of who should pay for the service of the EPD.

IT infrastructure for the EPD: a lucrative market for large companies

Against this backdrop, large corporations including Swiss Post and Swisscom are scenting a lucrative market in the development of IT structures. For example, Swisscom is a technology partner for numerous affinity domains and is working on solutions that will enable the establishment of the EPD in a number of cantons, including Zurich, Bern and Basel.

It remains unclear to what extent this close cooperation with industry will prove to be conducive to the national goal. Experts including Naef warn that providers of EPD platforms will develop their own ecosystems and thus create new monopolies. For example, Swisscom’s EPD services are not yet compatible with the solutions developed by Swiss Post. This torpedoes the objective of interoperability. Not least for this reason, the federal government is insisting on standards and central interfaces. In the meantime, Swiss Post has assigned its own eHealth developments over to Siemens Healthineers.

Regardless of whether the cantons are looking to finance the construction and operation of an affinity domain through state resources or are looking for business models, success depends largely on the activities of the cantons. AAAs a result, they have the support of the Swiss Conference of Cantonal Health Directors (GDK) in their efforts to push ahead with the introduction of the EPD. The GDK functions as an interest group for the cantons in health policy inasmuch as they formulate and defend their interests vis-à-vis the Federal Government and the National Council, and promote cooperation between the 26 cantons.

Despite the aforementioned complexity that Switzerland will have to resolve before a full-coverage EPD offer can be implemented, the last word of this arduous process could be a product of characteristic Swiss quality, with the patient as the owner of their health data, a secure source of information for the accumulated knowledge of their medical history, and a decentralized, federal as well as stable system. And although there are many uncertainties that remain to be resolved, the FOPH is sticking to its 2020 launch date for hospitals. The deadline is April 15th and the clock is ticking.

Note: This blog post was written in cooperation with Cinthia Briseño. She supports on-site research for the survey #SmartHealthSystems with her journalistic contributions to our blog.

The study is carried out by empirica Communication and Technology Research on behalf of the Bertelsmann Stiftung.

Follow us as we take a closer look at e-health developments in various countries for our study throughout the course of 2018.

We will publish the full results of our international study in November 2018. Until then, we will be highlighting thought-provoking insights and best practices from other countries here in our blog. If you are interested in keeping up-to-date with our latest analyses, we recommend that you sign up for our email newsletter: