As part of our #SmartHealthSystems study which examines the digital transformation of healthcare systems in 17 countries, we’ve visited five of these countries to take a closer look at what they’ve achieved. In each country, we’ve explored the political, cultural, technological and economic factors driving success as well as obstacles to advancing digitization strategies in healthcare. The findings of our cross-national study will be published in November 2018. Until then, we’ll be highlighting thought-provoking insights and best practices from other countries here in on our blog. Our look at Israel shows how a small nation has focused on big data in the healthcare sector for the last two decades – and with a giant database of patient information, also wants to become a paradise for international research.

About 8.4 million people live in Israel. That’s fewer than in Baden-Württemberg. Nevertheless, the country routinely draws the attention of the entire world; while this is certainly true in terms of politics, it’s also because the outside world casts a jealous eye on Israel’s achievements in digitization. Nowhere else are so many tech companies per capita founded, earning Israel the nickname of “start-up nation.” Some companies send entire delegations to the country for inspiration from its many founders and young firms, while corporate giants such as Apple, Google, Microsoft and IBM even operate research centers there.

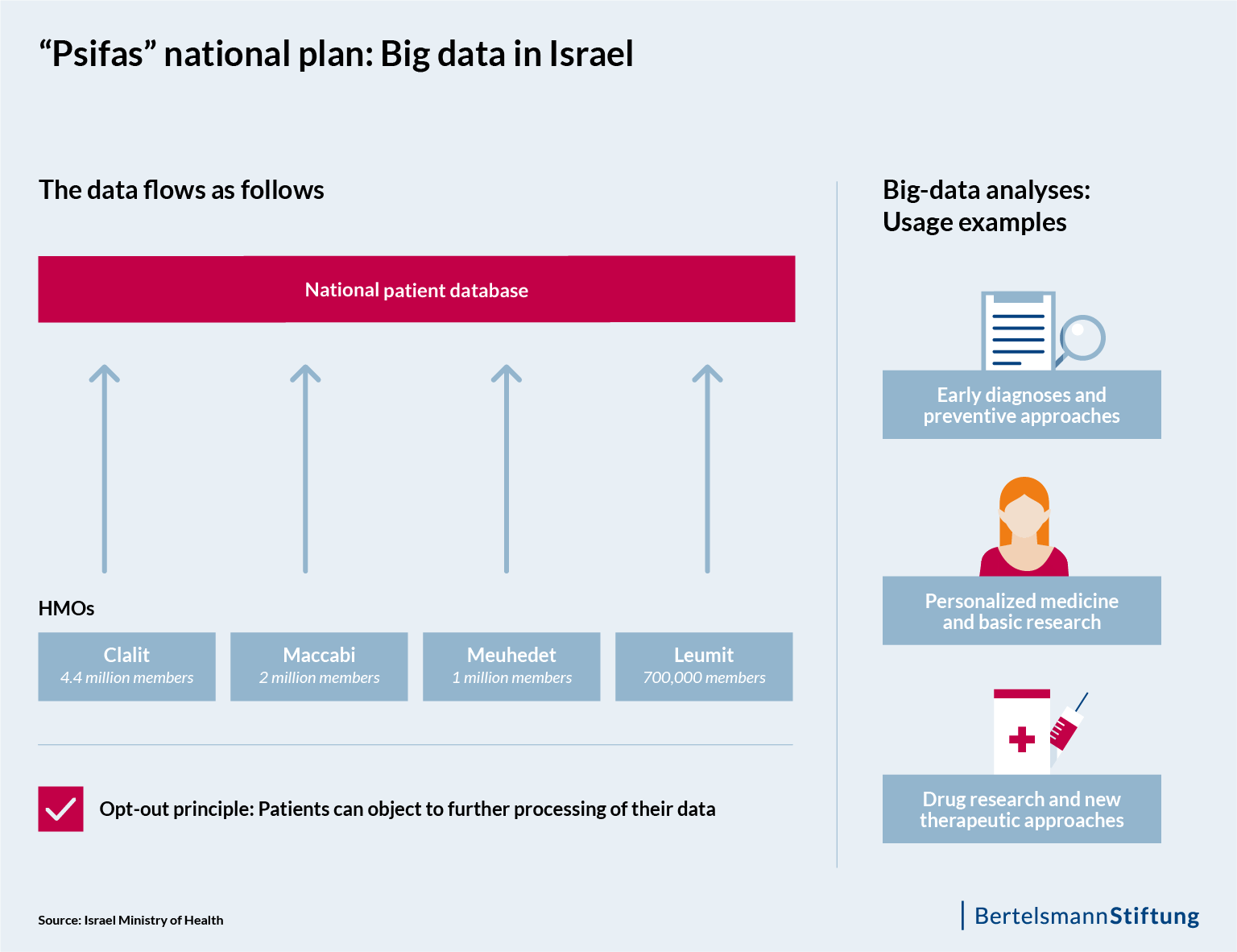

Israel is seeking to carve out a leading role in terms of healthcare digitization, too. In March, the Israeli government adopted a national five-year plan that foresees expenditures of around €232 million. The core of the plan is the “Psifas” (Mosaic) project, which aims to collect the medical data of virtually all Israeli citizens in a comprehensive digital patient database. Containing information on issues ranging from cancer, auto-immune conditions and mental disorders to the rarest diseases, the pool of data from more than eight million citizens will be processed anonymously, and will be provided to researchers, companies and medical start-ups for research purposes.

A project like “Mosaic” would almost inevitably meet with massive resistance in Germany. For Israel, by contrast, big data has, as an issue, long since ceased being a vision of the future, and a national patient database is essentially a logical next step. Patient data has already been digitally recorded and evaluated at clinics for more than two decades. According to the Israeli government, what will now follow is a combination of three things: very large databases, artificial intelligence (AI) and connectivity.

Big data: Long a feature of daily life for Israelis

All citizens residing in Israel are legally required to be a member of one of four state health maintenance organizations, or HMOs. These include Clalit, Maccabi, Leumit and Meuhedet. Along with insuring their members, these institutions provide a wide range of medical services themselves and operate a number of pharmacies and therapy centers around the country. Members pay a statutorily determined contribution, and are in turn entitled to a uniform catalog of services defined by the Ministry of Health.

Clalit also runs eight general and specialist clinics. With a share of about 54 percent of all insured, Clalit Health Services is top dog among the HMOs, and is thus Israel’s largest healthcare organization. It stores all its members’ data – from blood pressure and weights to data about diseases, therapies and medications – in patient records. The Clalit Research Institute (CRI), a research facility operated by Clalit, alone holds a wealth of data that includes health information from more than four million people.

As integrated healthcare providers and insurers, each of the four HMOs has a central data warehouse in which clinical and administrative data from most medical processes for all members is collected. The consolidation of these databases into the national patient database is being overseen by the Ministry of Health. Eleven pilot research projects are already underway. In addition, the HMOs as well as some of the state hospitals are conducting their own research programs with various focuses.

The CRI’s mission statement is simple: “Real people. Real data. Real change.” This claim could also succinctly sum up the principles underpinning Israel’s digital-healthcare agenda. The goal is to develop predictive models with the help of mountains of data on diagnoses, symptoms and disease stages. This in turn should enable better and more efficient diagnoses, therapies and preventive measures, all at lower cost.

To be sure, it is the ministry that is conducting and coordinating the construction of the nationwide infrastructure for the digital patient records – and only following pressure by the HMOs. However, the ministry otherwise rarely interferes in the HMOs’ affairs, and is very cautious with regard to its regulatory tasks. The government deliberately leaves the HMOs considerable freedom to engage in innovation and research projects.

As a consequence, each HMO has already developed its own algorithms aimed at deriving useful knowledge from its electronic files. Within Clalit, for example, patients at risk of kidney failure are identified at an early stage. Ordinarily, this is difficult for non-experts, as patients often show only small, difficult-to-interpret changes in their kidney functions. However, with the help of data analyses, the CRI has been able to develop a predictive model as well as specific guidelines and training programs for clinical physicians and has implemented these in its hospitals. Maccabi also has an algorithm in use that identifies people with an elevated risk of colorectal cancer on the basis of specific patient data. Following this algorithmic identification, a note alerting physicians to the high-risk status is made in the patient’s personal medical record. Physicians can then invite the affected individuals to undergo an in-office health screening in order to proceed with preventive care in the most effective possible way.

Interoperability over a decentralized network

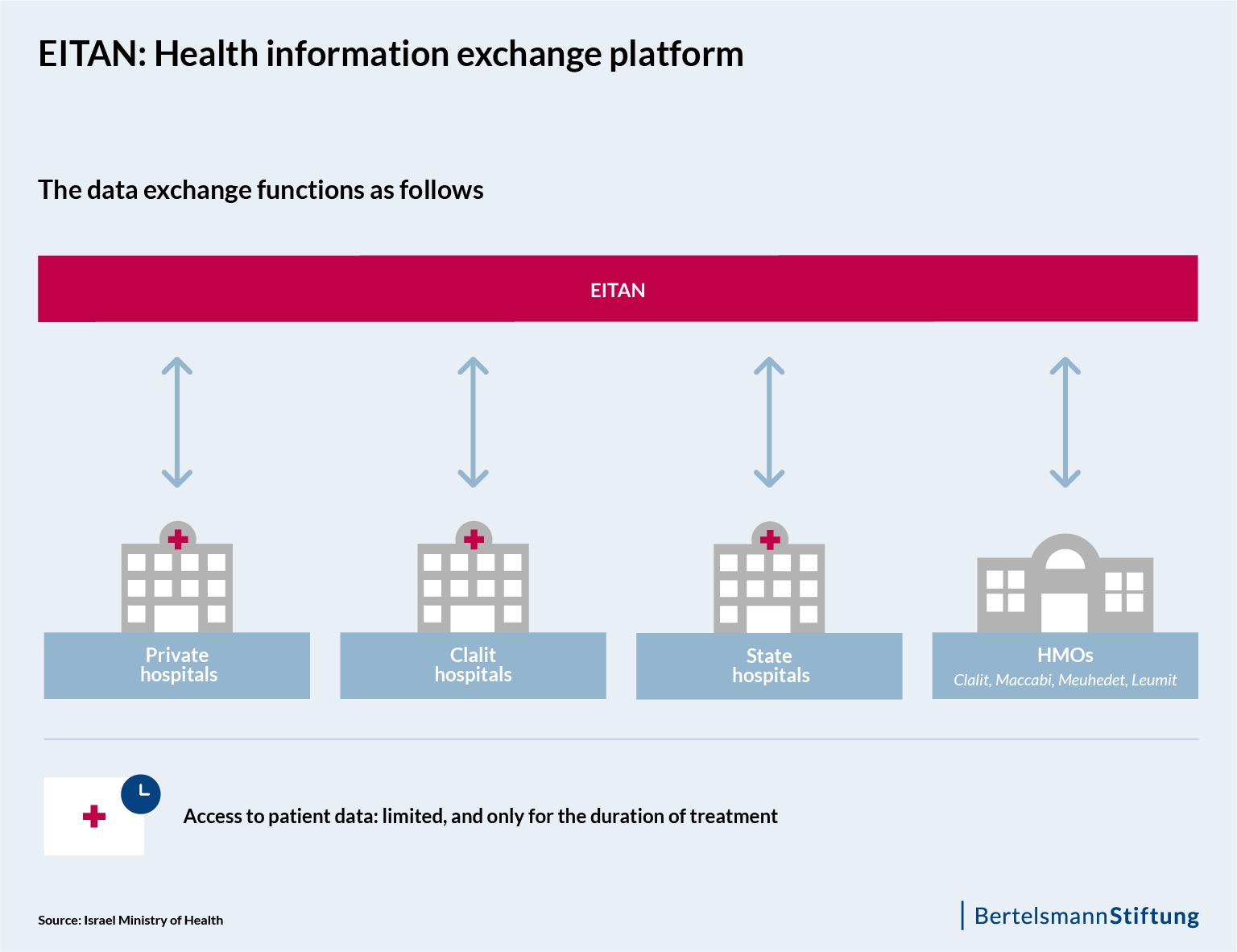

The Ministry of Health itself is also carrying out projects aimed at promoting the use of data-based decision-support systems. Moreover, it is responsible for the issue of data interoperability. To ensure that the numerous service providers and medical institutions always have access to the electronic patient data, the ministry has developed a special health information exchange (HIE) system called EITAN, which is currently being tested in a number of clinics. EITAN is based on OFEK, a system originally conceived by Clalit, but which is now being scaled up by the ministry across the entire country.

The planned EITAN system will serve an information-exchange function, consolidating important medical information from patients’ medical records at hospitals and HMOs. However, this will not take place in a central database. Rather, the data will be made available in a decentralized way, and will be managed by the ministry. If a patient enters a clinic, only those medical staffers who are caring for him or her will have access to the relevant personal medical data. Once the patient leaves the hospital, this access will expire after a certain time, during which any documentation has to be completed. The patient’s HMO then receives a report on the emergency-room visit or hospital stay.

Particularly sensitive health information, such as that regarding abortions, sperm donations or visits to psychiatric institutions, will not be delivered through the HIE. Additionally, patients have the ability to exclude their information from the network by making a request to their HMO. The exchange of information between a clinic and a rehabilitation facility, for example, can be prevented in this way. Only the HMO receives the final report on the clinic stay one more data point that an algorithm can use to develop new insights.

The world’s largest collection of medical data

The government’s plan to establish a national patient-information database is also drawing great interest from beyond the country’s borders. The world’s most comprehensive collection of medical data, with its information on millions of people, offers enormous potential for big-data analyses. The government expects income in the millions of euros resulting from the licensing of anonymized data.

And what about data protection? To be sure, there are isolated concerns with regard to data security and possible misuse. However, the government has declared that clear protective safeguards will be put in place to enforce patient privacy, information security and access restrictions. In addition, every citizen has the right to object to any further utilization of his or her data. Nevertheless, Israelis generally have little concern regarding the handling of private data. It is thus unclear how many people will in fact register objections of this kind.

Note: This blog post was written in cooperation with Cinthia Briseño. She supports on-site research for the survey #SmartHealthSystems with her journalistic contributions to our blog.

The study is carried out by empirica Communication and Technology Research on behalf of the Bertelsmann Stiftung.

Follow us as we take a closer look at e-health developments in various countries for our study throughout the course of 2018.

We will publish the full results of our international study in November 2018. Until then, we will be highlighting thought-provoking insights and best practices from other countries here in our blog. If you are interested in keeping up-to-date with our latest analyses, we recommend that you sign up for our email newsletter: